Some history…is what it is, history but every now and then you read some things that bring the message home clearer than others. Take for example the history we are about to share in regard to the weight indicator and how far we have come as an industry.

An industry that we are very proud to be part of that is full of enthusiasm, skill, engineering and candor.

If you are an experienced person that has spent years on the floor of any drilling rig this will be a very interesting read for you. If you are young and just starting out then here is a history lesson that you will probably not learn in school, especially as colorful as the author has put it here.

We appreciate those innovators who have come before us and the ones who are responsible for innovating our way through to the next generation, thank you for all that you do…

Below is a chapter from “Roughnecks, Rock Bits and Rigs” The Evolution of Oil Well Drilling Technology in Alberta, 1883 – 1970, written by Sandy Gow

The weight indicator was the first device put into service to assist the driller in making hole, running pipe, fishing, or operating ocher cools in the hole. In tine other instruments were employed in concert with the weight indicator, including the mud pressure gauges, tachometers which showed the speed of the rotary table and the torque on the drill string, improving both safety and efficiency.

The weight indicator was the first device put into service to assist the driller in making hole, running pipe, fishing, or operating ocher cools in the hole. In tine other instruments were employed in concert with the weight indicator, including the mud pressure gauges, tachometers which showed the speed of the rotary table and the torque on the drill string, improving both safety and efficiency.

The entire weight of the drill string could not be allowed to rest on the bit at the bottom of the hole. Some of this weight had to be borne by the hook. The weight indicator measured the weight of the drilling shaft when the bit was off the bottom of the hole, and the weight of the drilling shaft unsupported by the bit when drilling. There were two general types of weight indicators employed in Alberta, one of which was operated from the deadline and the other from the hook. Both types had indicating gauges, and some had recorders providing a permanent record of the weight carried on the bit, the pull on the pipe, and the round-trip data.

The need for weight indicators had been obvious for a number of years, but in their absence the driller himself functioned as the only "instrument" and he used whatever seemed to work best to determine what the load was. It was important to know how much pull was being exerted when a cable tool or rotary rig was pulling casing or drill pipe, because, from time-to-time, heavy weights on the line or hook caused the derrick to be "pulled in" on top of the crew.

This happened frequently enough that the crew would exit the derrick floor when a "hard pull" (heavy load) was necessary, especially when it was being done with a luff line, a set of block and tackle used to supplement the regular gear coupled to an underpowered, single cylinder steam engine when working or pulling casing. Roy Widney, a cable cool driller, brought several primitive procedures with him from the United States to southern Alberta. Widney commented that “the weight indicator was made up of some white marks on the leg of the derrick and an iron rod pushed through the deadline." The driller used his intuition, experience, and sometimes Widney's two crude indicators to measure the amount of pull being exerted on the line when a hard pull was taking place. The white marks measured the rig's squat level under load, while the rod in the deadline moved closer and closer to the floor as the load became heavier and heavier. An experienced driller also used his ears. As the hard pull proceeded the rig would groan, and, if snapping wood or squealing steel were heard, the procedure might stop. On the other hand, it might proceed with the hope that the rig would be able to withstand just a little bit more pull so that tools, casing, or drill pipe could be extracted. If not, the crew would scatter in an attempt to get clear before the crown block or even the whole derrick came down.

This happened frequently enough that the crew would exit the derrick floor when a "hard pull" (heavy load) was necessary, especially when it was being done with a luff line, a set of block and tackle used to supplement the regular gear coupled to an underpowered, single cylinder steam engine when working or pulling casing. Roy Widney, a cable cool driller, brought several primitive procedures with him from the United States to southern Alberta. Widney commented that “the weight indicator was made up of some white marks on the leg of the derrick and an iron rod pushed through the deadline." The driller used his intuition, experience, and sometimes Widney's two crude indicators to measure the amount of pull being exerted on the line when a hard pull was taking place. The white marks measured the rig's squat level under load, while the rod in the deadline moved closer and closer to the floor as the load became heavier and heavier. An experienced driller also used his ears. As the hard pull proceeded the rig would groan, and, if snapping wood or squealing steel were heard, the procedure might stop. On the other hand, it might proceed with the hope that the rig would be able to withstand just a little bit more pull so that tools, casing, or drill pipe could be extracted. If not, the crew would scatter in an attempt to get clear before the crown block or even the whole derrick came down.

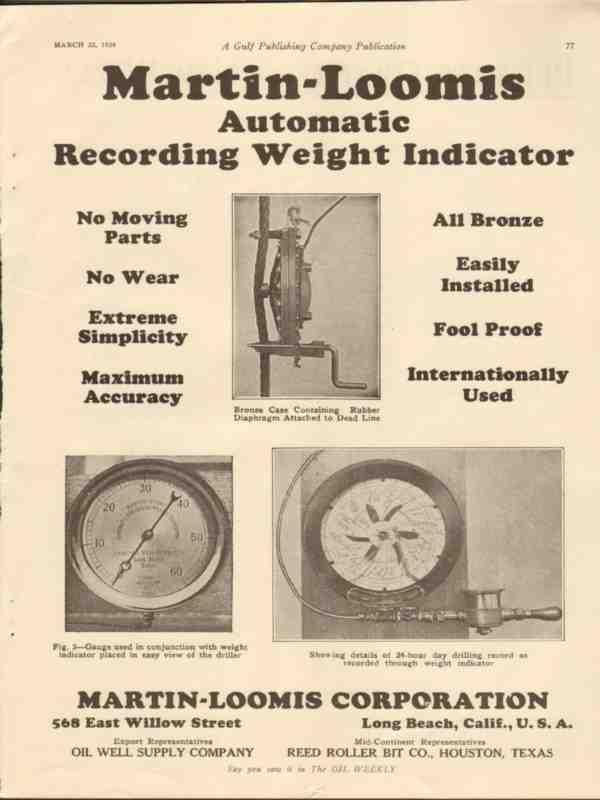

The first truly accurate weight indicator was marketed in 1930 by Martin-Loomis Company. The device measured the tension in the deadline that ran from the crown block sheave to the deadline tie-down anchor fixed to the derrick or the mast. The tension was recorded on a dial known as the "stool pigeon" which was in the driller's line of sight. Other companies developed their own models. The most common one used in Canada appears to have been the one sold by Martin-Decker, a successor company to Martin-Loomis. Known as the Quintuplex because it incorporated a recording weight indicator, a circulating pressure gauge, a rotary table tachometer, and a drill pipe torque indicator, all housed in a case attached to a post near the driller.

The first truly accurate weight indicator was marketed in 1930 by Martin-Loomis Company. The device measured the tension in the deadline that ran from the crown block sheave to the deadline tie-down anchor fixed to the derrick or the mast. The tension was recorded on a dial known as the "stool pigeon" which was in the driller's line of sight. Other companies developed their own models. The most common one used in Canada appears to have been the one sold by Martin-Decker, a successor company to Martin-Loomis. Known as the Quintuplex because it incorporated a recording weight indicator, a circulating pressure gauge, a rotary table tachometer, and a drill pipe torque indicator, all housed in a case attached to a post near the driller.

One common problem with all weight indicators was their response to rough usage and the weather. The intense vibration experienced by weight indicators, situated as they were as on the derrick floor, frequently caused the copper tubing carrying the fluid between the wire rope and the gauge's diaphragm and indicator needle to snap. In cold weather the rubber hose that housed and partially insulated the copper tubing could not prevent the fluid from freezing. In hot weather, the sun shone on these same lines and they expanded, causing the weight measurements to increase; when the lines were in the shade again, the values decreased. Problems with vibration and temperature sensitivity persisted for some years.

The Quintuplex was succeeded by the Martin Decker "Sealtite" weight indicator model which could simultaneously record weight, torque, mud pressure, rotary speed, and the rate of penetration. This unit was also clamped to the deadline at the top and bottom. A deflection plug caused the line to deflect. Increased tension in the deadline tended to straighten it, and increased the pressure against the deflection plug, which passed on the change to the diaphragm and then the indicator needle in the panel.

After 1935, two more weight instruments appeared on the marker and persisted, which improvements, into the late 1940s. The first of these was the Abercrombie weight indicator, attached to the deadline of a cable cool rig casing line or a rotary drilling line. It could be used to indicate the weight in handling casing in and out of the hole, on fishing jobs or retrieving stuck pipe, and to indicate the amount of weight resting on a rotating rock bit. This piece of equipment had the virtue of simplicity; it was entirely mechanical; and easy to connect to the deadline. The dial of this indicator read directly in pounds and could be adjusted to permit the driller to read more than one line. The second indicator to appeared in Alberta in the 1930s was the Line Scale Weight Indicator. Attached to the deadline of the casing or drilling line, it indicated the weight directly in pounds by multiplying the increase or decrease in the bend in the line when it was put under load. It used the mechanical force of a deflected line to actuate a lever (against resistance of a spring), which moved an indicator on the dial. It was said to be a "tiny bit hardier" than most other indicators.

The Cameron Iron Works entered the competition for weight indicators during the 1930s and brought out several models before producing a sturdy one in the form of their Type C. It was a completely mechanical model with no recorder and was clamped to the deadline. The Cameron model Type E was similar to the Type C and also clamped co the deadline, but it differed in that it measured directly into pounds rather than a scale of numbers indicating a degree of heaviness.

The Hook-Load indicator, employing both hydraulic and electric or electronic operating principles, appeared in the early 1950s. Manufactured by the Byron Jackson Company, it measured strain in the hook through the use of resistant type electric strain gauges placed on the load-carrying equipment. After some teething problems, they became a viable alternative to the line-type weight indicators.

Martin Decker Corporation and National Supply Company developed a weight indicator using a completely new operating principle. It was known as the Type D Combination Weight Indicator and Wire Line Anchor. The Wire Line Anchor was a pair of levers, one of which formed the base and was fixed to the rig floor or derrick foundation, while the other formed a wheel or drum around which the deadline was snubbed with two or three turns. Loads applied to the deadline rotated the drum within the limit of a series of stops. The two levers were joined at their extreme ends by a hydraulic pressure transformer which resisted the rotational force of the drum. The rotational force was thereby transformed into hydraulic pressure, which in turn was transmitted to a gauge and recorder at the driller's position. Hook load was shown in thousands of pounds. This line was more trouble-free than previous ones, according to George Fyfe, although it was also expensive and at first, not all rig owners were eager to put out the money to buy one.

By 1958, three types of weight indicators were on the marker: Those based on the hook load principle; instruments attached to the deadline; and an instrument composed of a pressure transformer and indicating gauge connected by a hydraulic hose. George Fyfe confirms that eventually this third type of instrument became the most favored because it was more reliable and more rugged than the older models in a business where reliability and the ability to withstand rough handling are paramount.

“Roughnecks, Rock Bits and Rigs” The Evolution of Oil Well Drilling Technology in Alberta, 1883 – 1970, written by Sandy Gow ISBN 1-55238-067-x

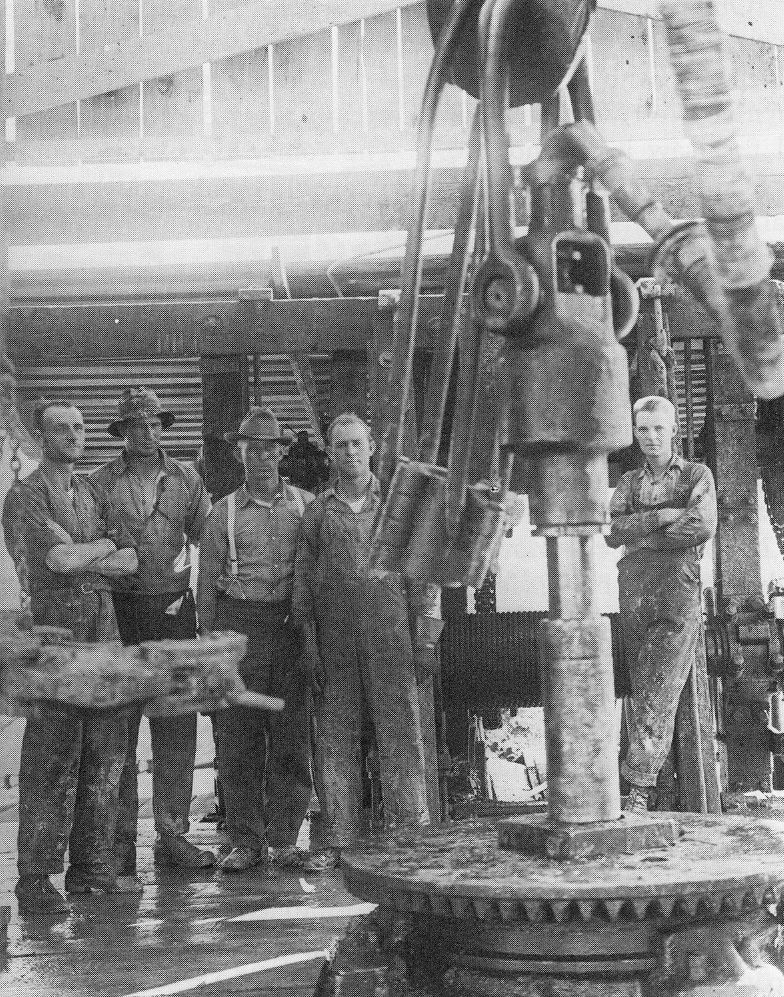

Article thumbnail photo: 1920’s Steam Powered Core Drill Rig – Jeff Hyatt