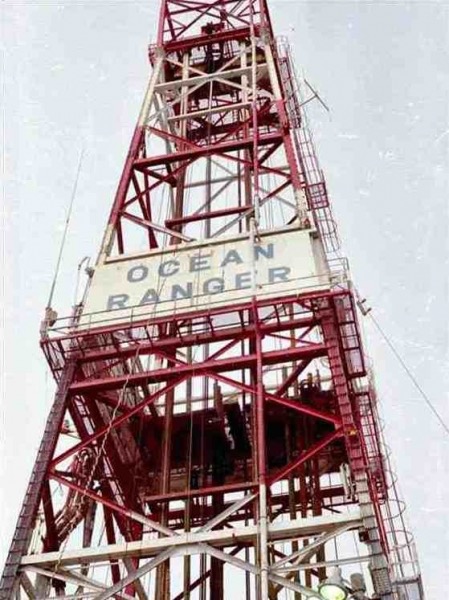

February 15th marks the anniversary of the 1982 ODECO Ocean Ranger drilling rig disaster in which 84 offshore workers lost their lives.

ODECO Ocean Ranger

Ocean Ranger was a semisubmersible drilling rig, designed to operate in the world’s harshest offshore environments, with the capacity to withstand wind speeds of 100 knots (190 km/h) and wave heights of 110 feet (34m).

Through its design and build, the self-propelled Ocean Ranger was classified for unrestricted ocean operations; with US owners ODECO boasting that Ocean Ranger was the world’s largest semi-submersible oil rig to date upon delivery in 1976.

With the ability to operate in water depths of up to 1,500 feet (460m) and drill to a maximum depth of 25,000 feet (7,600m), the 25,000 tonne rig could accommodate 100 workers, ensuring it was employed on North America’s largest offshore drilling projects.

Ocean Ranger Sinking

Ocean Ranger was on hire to Mobil Oil of Canada Ltd, during a rush of activity offshore eastern Canada, as exploration and production companies were attempting to map out the now giant Hibernia oil field.

Located in the North Atlantic, approximately 196 miles (315km) offshore Newfoundland; the area is renowned for its harsh environment where hurricane force winds, rouge waves and icebergs are commonplace.

Ocean Ranger along with two other semisubmersible drilling rigs, the Sedco 706 and the Zapata Ugland, had been drilling exploration wells in the area for Mobil Oil throughout 1981.

Ocean Ranger had completed its second well on the project late 1981 before spudding its third, well J-34, on the 26th November 1981. Drilling continued throughout the North Atlantic winter with Ocean Ranger remaining on J-34.

On 14th February all three rigs received warnings of an incoming weather front, connected to an Atlantic Cyclone, due to hit later that day and continue throughout the night.

Timeline of Events.

Sunday 14th February

1630 – In line with procedure, drilling operations were stopped on the Ocean Ranger, and the crew prepared to hang-off (a process of disconnecting both drillstring and riser from the well). Due to the speed of the storm’s approach, the drill crew were forced to shear the drill string with the BOP ram, and leave the riser disconnect until later that evening.

1900 – Both the Sedco 706 and Zapata Ugland reported being hit by a large rouge wave that caused damage to both. The Sedco 706 reported the loss of one lifeboat.

Shortly after the two rigs had reported via marine radio, intermittent radio transmissions were herd between the Ocean Ranger’s crew mentioning a broken port light and water ingress.

2100 – The Ocean Ranger was raised via radio and confirmed to both rigs and standby vessels in the area that it had suffered a broken port light (porthole) to its ballast control room; and that sea water ingress had caused some damage to its ballast control panel. Ocean Ranger’s radio operator also reported problems with the rigs ballast control, due to the panel’s water ingress, with some ballast tank valves opening and closing autonomously. However, both rigs and all vessels within the area reported that Ocean Ranger had the situation under control and that for the remainder of the evening normal radio communications continued between all with nothing to report.

2330 – Ocean Ranger transmitted its scheduled weather report to the onshore base, on time, with no indication of any problems.

Monday 15th February

0052 – Ocean Ranger sent a Mayday call, reporting a serious list of between 10 to 15 degrees, and requested immediate assistance. This was the first report of Ocean Ranger suffering serious problems.

Ocean Ranger’s standby boat attempted to get in close to the rig but was unable due to the force of the storm.

0100 – Mobil’s onshore management were alerted, in turn alerted the Canadian Armed Forces, who attempted to mount a helicopter rescue.

Standby vessels form both Sedco 706 and the Zapata Ugland were sent to the scene to assist in the rescue attempt.

0130 – All stations received their final radio transmission from Ocean Ranger, “There will be no further radio communications from Ocean Ranger. We are going to lifeboat stations.”

Ocean Ranger is believed to have been abandoned by its crew shortly after with no rescue party able to reach them.

Post Abandonment

0221 – Ocean Ranger’s standby vessel Seaforth Highlander reported seeing flares from a badly damaged lifeboat and managing to attach a line between the two.

With the vessels crew attempting to pull men to safety, the line snapped, allowing waves to overcome and capsize the lifeboat.

0230 – The first helicopter arrived on location after being beaten back by the storm.

0245 – The second standby vessel arrived on location and reported no persons or lifeboats visible onboard Ocean Ranger now listing heavily.

Sinking

Ocean Ranger is believed to have sunk between 0307 and 0313, just over three hours after sending its initial distress signal.

All 84 personnel onboard the rig, 46 Mobil employees and 38 from contracting companies, died in the incident.

Only 22 bodies were ever recovered.

Investigations

The Royal Commission

A Royal Commission was setup, that found multiple failures within the Canadian offshore industry.

In particular the commission found the industry operated without any form of mandatory and regulated safety training for offshore workers, or any similar training for crew in positions of operating the rigs safety systems, which was often left to on-the-job training.

The commission also found a lack of safety and survival equipment, onboard the rig, including abandonment suits.

Design faults were also found with the drilling rig itself, namely the location of the posthole in a vulnerable location, at the ballast control room, down the rig’s leg.

US Coast Guard Investigation

The US Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation conducted a concurrent investigation into the actual events of the incident and concentrated heavily on the design of the Ocean Ranger.

They reported that in their belief the events occurred as followed:

- A large wave appeared to cause a broken portlight.

- The broken portlight allowed the ingress of sea water into the ballast control room.

- The ballast control panel malfunctioned or appeared to malfunction to the crew.

- As a result of this malfunction or perceived malfunction, several valves in the rig’s ballast control system opened due to a short-circuit, or were manually opened by the crew.

- Ocean Ranger assumed a forward list.

- As a result of the forward list, boarding seas began flooding the forward chain lockers located in the forward corner support columns.

- The forward list worsened.

- The pumping of the forward tanks was not possible using the usual ballast control method as the magnitude of the forward list created a vertical distance between the forward tanks and the ballast pumps located astern that exceeded the suction available on the ballast system’s pumps.

- Detailed instructions and personnel trained in the use of the ballast control panel were not available.

- At some point, the crew blindly attempted to manually operate the ballast control panel using brass control rods.

- At some point, the manually operated sea valves in both pontoons were closed.

- Progressive flooding of the chain lockers and subsequent flooding of the upper deck resulted in a loss of buoyancy great enough to cause the rig to capsize.

Offshore Safety Changes

Much like the Alexander L. Kielland disaster, in Norwegian waters less than two years before, the subsequent investigation by The Royal Commission paved the way for huge change within Canada’s offshore industry; bringing in a raft of regulatory changes and standards for operators and workers on the nations continental shelf to abide by.

Changes and improvements in safety and working practices have gone on to save countless lives and continue to make the industry one of the safest in the world.

Join our mailing list here